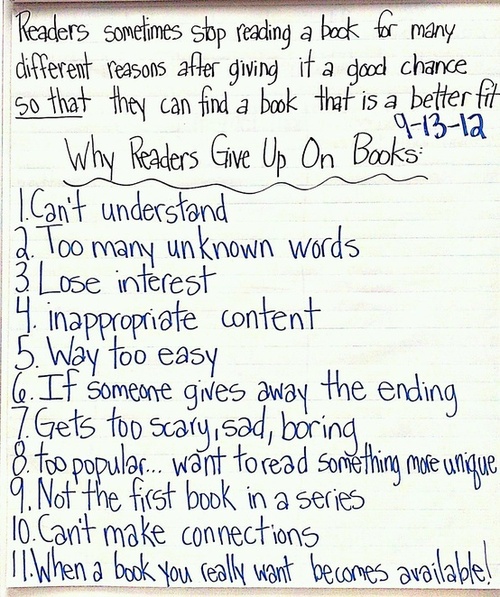

Category Archives: Reading

Stop Reading Reasons

Discussion Tables

Discussion tables. Pick a passage from a book you are reading {read aloud, book club book, etc.} and glue it to the center of bulletin board paper and have the students write their thoughts about the passage and respond to their classmates.

Note to self: Use for group annotations/annotating passages

When kids can’t read (grade 6-12)

When Kids Can’t Read: What Teachers Can Do

By Kylene Beers (Heinemann, 2003)

PDF: http://middlesecondarytoolkit.pbworks.com/f/mainidea111509.pdf

Online Books

Here are a bunch of links to places that have free online books for you to use as a read aloud or for a listening center.

http://www.storylineonline.net/

http://www.storynory.com/ – myths and legends

http://www.openculture.com/freeaudiobooks

http://www.booksshouldbefree.com/ – middle school

Edited out bronken links from this post:

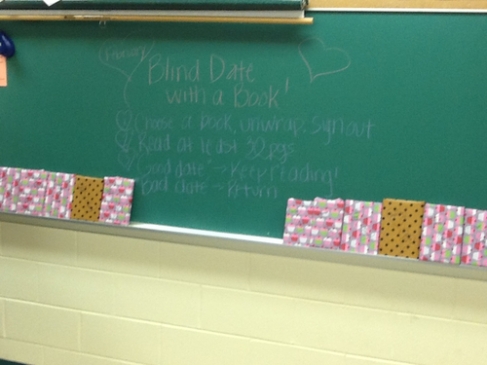

Blind Date with a Book!

You know I will do ANYTHING to help my boost interest in reading in my 7th/8th grade classes. Last week I saw a post making the rounds about a library that wrapped books and put just a few key words on the front (of course, now I can not find that post for the life of me! If you know of it, please let me know! I give ALL the credit to their fantastic idea!).

I decided that would be great for my room, as all the hormones are raging!

“Blind Date with a Book”

1. Read the key words, pick a book, and go see Miss before you unwrap.

2. Wrap and see what you picked!

3. Read at least 30 pages – if you decide that your “date” is going well and you want to see where it leads, keep reading! If your date is “nice, but not for you”, return the book.

Luckily, I found this adorable Valentine’s wrapping paper at Target (honestly, where else?!) to make things festive. Some of the tags include: fast paced, action, 1st person narrative, inspiring, dark, page turner, popular author, brand new, now a movie, etc.

Here’s hoping to fun times and good reads!

http://classroomcollective.tumblr.com/tagged/Reading/page/3

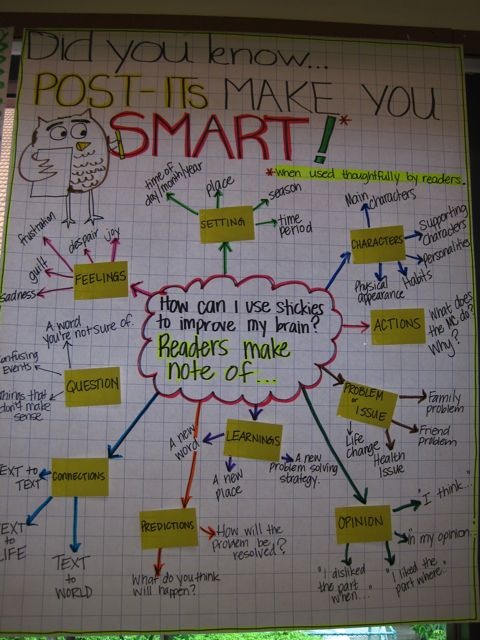

Readers make note of

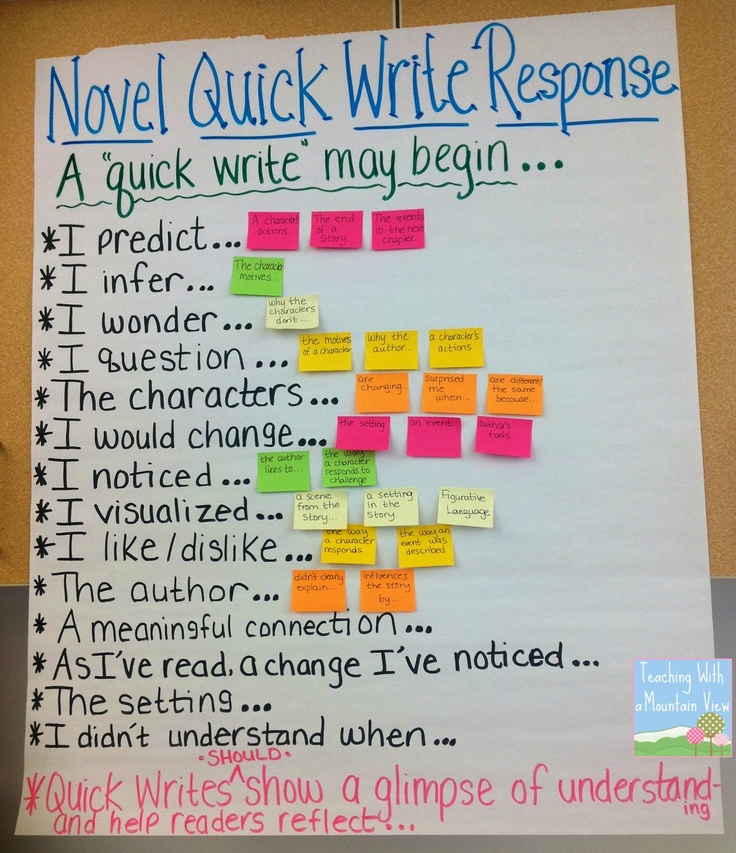

Photo is a little difficult to read but I liked the idea of using post its to create this chart–it would engage the students–get them thinking about about the process of active reading and the chart would be a useful resource for them to refer to/have in their reader/writer notebook.

Metaphors

The Magic of Metaphor: What Children’s Minds Teach Us about the Evolution of the Imagination

by Maria Popova

Full article here: http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2013/08/19/james-geary-i-is-an-other-children-metaphor/

“Metaphorical thinking … is essential to how we communicate, learn, discover, and invent.”

“Children help us to mediate between the ideal and the real,” MoMA’s Juliet Kinchin wrote in her fascinatingdesign history of childhood. Indeed, children have a penchant fordisarming clarity and experience reality in ways profoundly different from adults, in the process illuminating the workings of our own minds. But among the most curious of these mediations of reality is children’s understanding of abstraction in language, which is precisely whatJames Geary explores in a chapter of his altogether enthralling I Is an Other: The Secret Life of Metaphor and How It Shapes the Way We See the World (public library).

But first, Geary examines the all-permeating power of metaphor:

Metaphor is most familiar as the literary device through which we describe one thing in terms of another, as when the author of the Old Testament Song of Songs describes a lover’s navel as “a round goblet never lacking mixed wine” or when the medieval Muslim rhetorician Abdalqahir Al-Jurjani pines, “The gazelle has stolen its eyes from my beloved.”

Yet metaphor is much, much more than this. Metaphor is not just confined to art and literature but is at work in all fields of human endeavor, from economics and advertising, to politics and business, to science and psychology. … There is no aspect of our experience not molded in some way by metaphor’s almost imperceptible touch. Once you twig to metaphor’s modus operandi, you’ll find its fingerprints on absolutely everything.

Metaphorical thinking – our instinct not just for describing but for comprehending one thing in terms of another, for equating I with an other – shapes our view of the world, and is essential to how we communicate, learn, discover, and invent.

Metaphor is a way of thought long before it is a way with words.

Children, it turns out, are on the one hand skilled and intuitive weavers of original metaphors and, on the other, utterly (and, often, humorously) stumped by common adult metaphors, revealing that metaphor is both evolutionarily rooted and culturally constructed. Citing a primatologist’s study of a bonobo, humans’ closest living relative, who was able to construct simple metaphors after learning to use symbols and a keyboard, Geary traces the developmental evolution of children’s natural metaphor-making ability:

Children share with bonobos an instinctive metaphor-making ability. … Most early childhood metaphors are simple noun-noun substitutions… These metaphors tend to emerge first during pretend play, when children are between the ages of twelve and twenty-four months. As psychologist Alan Leslie proposed in his theory of mind, children at this age start to create metarepresentations through which they imaginatively manipulate both the objects around them and their ideas about those objects. At this stage, metaphor is, literally, child’s play. During pretend play, children effortlessly describe objects as other objects and then use them as such. A comb becomes a centipede; cornflakes become freckles; a crust of bread becomes a curb.

Children’s natural gift for rich and vivid metaphors, Geary argues, is propelled by the same driving force of our own adult creativity, pattern-recognition. Because kids’ pattern-recognition circuits aren’t yet stifled by narrow conventions of thinking and classification, they are able to produce a cornucopia of metaphorical expressions – but only few of them actually make sense. The reason is that successful metaphors hang on perceptual similarities, and in the best of them these similarities are more abstract than literal, but children are only able to comprehend the more obvious similarities as their developmental psychology evolves toward abstraction. Geary cites an illustrative study:

Children listened to short stories that ended with either a literal or metaphorical sentence. In a story about a little girl on her way home, for example, the literal ending was “Sally was a girl running to her home,” while the metaphoric ending was “Sally was a bird flying to her nest.”

Researchers asked the children to act out the stories using a doll. Five- to six-year-olds tended to move the Sally doll through the air when the last sentence was “Sally was a bird flying to her nest,” taking the phrase literally. Eight- to nine-year-olds, however, tended to move her quickly across the ground, taking the phrase metaphorically.

In his brilliant picture-book People, French illustrator Blexbolex uses visual, perceptual similarities to make clever commentary on conceptual ideas.

Another study, conducted by legendary social psychologist Solomon Asch and his collaborator Harriet Nerlove in the 1960s, demonstrated a different facet of the same phenomenon by testing children’s comprehension of so-called “double function terms,” such as “warm,” “cold,” “bitter,” and “sweet,” which in their literal sense refer to physical sensations, but in the abstract can describe human temperament and personality:

To trace the development of double function terms in children, Asch and Nerlove presented groups of kids with a collection of different objects – ice water, sugar cubes, powder puffs – and asked them to identify the ones that were cold, sweet, or soft. This, of course, they were easily able to do.

Asch and Nerlove then asked the children, Can a person be cold? Can a person be sweet? Can a person be soft? While preschoolers understood the literal physical references, they did not understand the metaphorical psychological references. They described cold people as those not dressed warmly; hard people were those with firm muscles. One preschooler described his mother as “sweet” but only because she cooked sweet things, not because she was nice.

Asch and Nerlove observed that only between the ages of seven and ten did children begin to understand the psychological meanings of these descriptions. Some seven- and eight-year-olds said that hard people are tough, bright people are cheerful, and crooked people do bad things. But only some of the eleven- and twelve-year-olds were able to actually describe the metaphorical link between the physical condition and the psychological state. Some nine- and ten-year-olds, for instance, were able to explain that both the sun and bright people “beamed.” Children’s metaphorical competence, it seems, is limited to basic perceptual metaphors, at least until early adolescence.

Younger children’s inability to understand how a physical state could be mapped onto a psychological one, Geary argues, has to do with kids’ lack of life experience in observing how physical circumstances – like, say, poverty or violence – can impact a person’s character, which, as we know, is constantly evolving and responsive to life:

Children have trouble understanding more sophisticated metaphors because they have not yet had the life experiences needed to acquire the relevant cache of associated commonplaces.

What this tells us is that while the hardware for making metaphors may be in-born, the software is earned and learned through living. This learning, Geary explains by pointing to cognitive scientist Dedre Gentner’s work, takes place in stages marked by a “sliding scale of increasingly complex similes:”

[Gentner] presented three different age groups – five- to six-year-olds, nine- to ten-year-olds, and college students – with three different kinds of similes.

Attributional similes, such as “Pancakes are like nickels,” were based on physical similarities; both are round and flat. Relational similes, such as “A roof is like a hat,” were based on functional similarity; both sit on top of something to protect it. Double similes, such as “Plant stems are like drinking straws,” were based on physical as well as functional similarities; both are long and cylindrical and both bring liquid from below to nourish a living thing.

Gentner found that youngsters in all age groups had no problem comprehending the attributional similes. But only the older kids understood the relational and double similes. In subsequent research, Gentner has found that giving young children additional context enhances their ability to pick up on the kind of relational comparisons characteristic of more complex metaphors.

Some of history’s most celebrated children’s books, like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, are woven of metaphors exploring life’s complexities.

Thus, as children’s cognition develops and their understanding of the world evolves, their metaphorical range becomes more expansive – something equally true of us grown-ups, as Geary reminds us:

Any metaphor is comprehensible only to the extent that the domains from which it is drawn are familiar.

But this is where it gets most interesting: While this familiarity might be the foot in the door of understanding, a great metaphor is also an original one, thus forming new, uncommon associations of common elements rather than relying merely on the familiar ones – a beautiful manifestation of combinatorial creativity at play. And therein lies the magic:

This is one of the marvels of metaphor. Fresh, successful metaphors do not depend on conventional pre-existing associations. Instead, they highlight novel, unexpected similarities not particularly characteristic of either the source or the target – at least until the metaphor itself points them out.

I Is an Other is endlessly illuminating in its entirety, exploring how metaphors influence our experience and understanding of everything from politics to science to money. It follows Geary’s equally fascinatingThe World in a Phrase: A History of Aphorisms and Geary’s Guide to the World’s Great Aphorists.

Rules of Writing – Elmore Leonard

Elmore Leonard: The Beloved Author’s 10 Rules of Writing

“If it sounds like writing … rewrite it.”

He prefaces [book] the list with a short disclaimer of sorts:

These are rules I’ve picked up along the way to help me remain invisible when I’m writing a book, to help me show rather than tell what’s taking place in the story. If you have a facility for language and imagery and the sound of your voice pleases you, invisibility is not what you are after, and you can skip the rules. Still, you might look them over.

Leonard then goes on to lay out the ten commandments, infused with his signature blend of humor, humility, and uncompromising discernment:

- Never open a book with weather.

If it’s only to create atmosphere, and not a character’s reaction to the weather, you don’t want to go on too long. The reader is apt to leaf ahead looking for people. There are exceptions. If you happen to be Barry Lopez, who has more ways to describe ice and snow than an Eskimo, you can do all the weather reporting you want.

- Avoid prologues.

They can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword. But these are ordinarily found in nonfiction. A prologue in a novel is backstory, and you can drop it in anywhere you want.

There is a prologue in John Steinbeck’s Sweet Thursday, but it’s O.K. because a character in the book makes the point of what my rules are all about. He says: “I like a lot of talk in a book and I don’t like to have nobody tell me what the guy that’s talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks. . . . figure out what the guy’s thinking from what he says. I like some description but not too much of that. . . . Sometimes I want a book to break loose with a bunch of hooptedoodle. . . . Spin up some pretty words maybe or sing a little song with language. That’s nice. But I wish it was set aside so I don’t have to read it. I don’t want hooptedoodle to get mixed up with the story.”

- Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue.

The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But said is far less intrusive than grumbled, gasped, cautioned, lied. I once noticed Mary McCarthy ending a line of dialogue with “she asseverated,” and had to stop reading to get the dictionary.

- Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said” …

…he admonished gravely. To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin. The writer is now exposing himself in earnest, using a word that distracts and can interrupt the rhythm of the exchange. I have a character in one of my books tell how she used to write historical romances “full of rape and adverbs.”

- Keep your exclamation points under control.

You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose. If you have the knack of playing with exclaimers the way Tom Wolfe does, you can throw them in by the handful.

- Never use the words “suddenly” or “all hell broke loose.”

This rule doesn’t require an explanation. I have noticed that writers who use “suddenly” tend to exercise less control in the application of exclamation points.

- Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly.

Once you start spelling words in dialogue phonetically and loading the page with apostrophes, you won’t be able to stop. Notice the way Annie Proulx captures the flavor of Wyoming voices in her book of short storiesClose Range.

- Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

Which Steinbeck covered. In Ernest Hemingway’s Hills Like White Elephants what do the “American and the girl with him” look like? “She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.” That’s the only reference to a physical description in the story, and yet we see the couple and know them by their tones of voice, with not one adverb in sight.

- Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

Unless you’re Margaret Atwood and can paint scenes with language or write landscapes in the style of Jim Harrison. But even if you’re good at it, you don’t want descriptions that bring the action, the flow of the story, to a standstill.

And finally:

- Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

A rule that came to mind in 1983. Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. What the writer is doing, he’s writing, perpetrating hooptedoodle, perhaps taking another shot at the weather, or has gone into the character’s head, and the reader either knows what the guy’s thinking or doesn’t care. I’ll bet you don’t skip dialogue.

by Maria Popova

http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2013/08/21/elmore-leonard-10-rules-of-writing/

Quick Write sentence starters

Novel Quick Write Anchor Chart